The Pattern of History in Live-Service Games

I don’t keep it a secret in these posts about how much I’ve fallen in love with Fortnite over the past few years, and how much of my gaming diet is composed of it. I also don’t think I have ever shied away from the fact that I still play Destiny 2, Final Fantasy XIV, World of Warcraft, Halo Infinite... and so on and so forth. I even held onto Overwatch until sometime around Spring of this year.

What I’m saying is, unfortunately, I get a lot out of games that the industry has come to dub as “live-services.” Games that (are supposed to) receive regular updates, usually within a seasonal model, and try to sap away as much of your time as they physically can so that you’re enticed to spend money on Battle Passes and cosmetic items.

I suppose it’s easy to theorize that the reason I like these games so much is because they are literally designed to psychologically compel you to return. They’re supposed to be addictive and FOMO-inducing enough to keep you in their ecosystem and spending money. Although I also tend to play these games because they are actually fun, and in a matter which is likely related to their predatory player retention tactics, they’re also usually the easiest to play with friends.

Despite being a person who claims to prefer a tightly-wound linear singleplayer experience, probably 90% of my time with games is spent playing multiplayer stuff. I’ll grind through ranks in competitive shooters, and I’ll dedicate entire weekends to the latest early-access survival/crafting shlock on Steam-- so long as my friends are there. The point is obvious. I enjoy playing these games because I get to have fun, connect, and make memories with the people I care about. Genuinely some of the best times I’ve spent with siblings, friends, and even partners, have taken place in games like Minecraft and PUBG.

However, the tricky part about spending so many years within the ecosystems of these live-services is that over time the games you’ve made so many memories with will eventually change, potentially even into something unrecognizable. The developers could make changes that alienate you to the point where you have to leave the game behind entirely.

Like I said, I dropped Overwatch earlier this year. I really didn’t want to. In fact, I think the game is still fun. It just progressed too far in a direction away from the game that I had initially fallen in love with. And, due to the nature of these live-services being typically online-only experiences, there’s not really a way to revisit those old versions without the effort of getting onto player-run private servers, if the community even decides to figure out the logistics of putting one together.

The only feasible way to go back to old spaces and sometimes even whole games that mean a lot to you, or that were simply just... better, is if the developer of said live-service is gracious enough to bless their audience with a re-release of some kind.

What I’m interested in is the fact that when they do it can go really well for them. More succinctly, what I’m most interested in is that inevitably... they all have to do it.

THE FLAT CIRCLE

In the now-distant year of 2013, the MMO RuneScape was one of the first notable examples of this that I can remember.

The version of that game which most players remembered fondly existed sometime around 2007. We all know it, we all fumbled around with its earlier browser-based incarnations at some point on the family computer, I’m sure. Over the course of a dozen or so updates which hoped to curb real-world trading and gambling using in-game currency, the things that players loved about the game were slowly eroded. And eventually graphical overhauls did away with the game’s primitive yet iconic presentation, and finally a complete mechanical rework of Runescape’s combat to mimic something more in-line with contemporary MMOs had rendered the game into being something completely different. Along with these updates, which culminated in what is now referred to as RuneScape 3, there were also swaths of in-game microtransactions for cosmetic and usable items alike.

These changes almost entirely alienated the original player base of the game and led to the creation of dozens of private servers where players could still experience the game as they once knew it.

Eventually in 2013, in another attempt to curb outside actors making money off of their product, there was an official referendum held by the developer, JAGEX, asking players to show their interest in a potential revival for the game exactly as it was in 2007.

Of course, it was met with wildly positive responses, and a new SKU of RuneScape, called Oldschool RuneScape, was officially re-hosted and maintained by a small team at JAGEX.

This would have been fine enough for players to come back and spend some time reliving the old days, reuniting with friends, and poking around at something so important to their childhoods. However, these returning players eventually ran into an issue that tends to arise with all of these games that attempt similar re-launches. Once the nostalgia had worn off, and players really got to spend some time with Old School RuneScape, they quickly realized that it was a solved game.

How players were able to spend so much time with RuneScape when they were younger, and why the world felt so big, and why they felt like they were more free to experiment with the game’s mechanics was simply because they didn’t know as much as we do now. Or did... in 2013.

Best in slot items? Solved. Best strategies for defeating bosses? Solved. Best healing, best PvP tactics, best methods for training skills, best ways to make money? All of it was solved before the Oldschool servers were even open. As a result, players burned through content in a matter of months that they had once spent literal years working through when they were stupid children.

This seemed to be an expected fate for a server like this one, and most assumed that those who came back would leave, and those who popped over from Runescape 3 to relive the glory days would go back over there.

This was the case until JAGEX devised an interesting solution.

With the launch of Oldschool RuneScape there was an adamant policy of, “no changes,” to ensure that the game people were playing was exactly the one they remembered from 2007. However the small team that was tasked with maintaining Oldschool RuneScape desired to make a few small tweaks-- quality of life changes that didn’t really affect the actual gameplay in any way. We’re talking about stuff like alternate inputs for moving the camera, or a larger suite of optional graphics options. But still, they couldn’t just add these things without angering the playerbase.

So eventually this team introduced a polling system wherein the players of Oldschool RuneScape would need a 75% majority in order to have any changes made to the game. This would ensure that an almost overwhelming majority of the players approved of the additions, while also allowing these developers to make changes that made the game better.

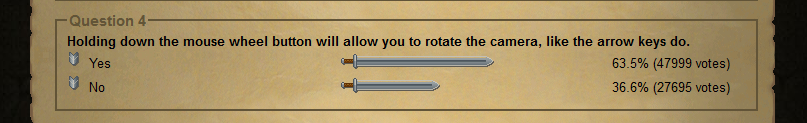

Lots of polls failed for content big and small alike. Famously an optional ability to move the in-game camera using your mouse, a function which is normally exclusively bound to the arrow keys on your keyboard, did not pass in its initial phases of polling. Ridiculous as it sounds, this was the most dedicated players of this version of the game trying to ensure that any updates coming to it would stay in line with what they perceived as the design philosophies at the core of the experience.

Eventually however, after players relaxed a bit and some changes were made to the polling system, brand new and substantive content was produced for these classic servers. Crucially, content that was never in the original version of the game which ended up becoming RuneScape 3.

Effectively there were now two different versions of the game that were branching out from the same starting point. Both of which are still supported separately and played to this day by two distinct groups of players. The interesting outcome of this is that at the time of writing this piece Oldschool RuneScape maintains over four times the number of players of its “modern” counterpart.

And while I don’t think this event was so massive that it taught the entire industry a lesson, it is an interesting microcosm for a recurring pattern that we see whenever one of these live services makes a similar move.

World of Warcraft, the biggest MMO of all time, currently exists on a similar series of content branches. The retail experience, and a batch of servers dedicated to hosting an old version of the game referred to as, “WoW Classic.” Similarly to RuneScape, when these Classic servers first opened it was met with massive success. Dozens of servers hosting the game as it was in 2004, so overloaded that each one was locked behind login queues which lasted upwards of 8-10 hours. However, over the course of a few months, players quickly burned through this old content and clamored for more.

WoW’s situation is a bit different, in that their of the game did slowly begin to reintroduce content in the order that it was released. Patches and expansions eventually came over the course of a few years, and ironically, it was just recently announced that WoW: Cataclysm would be coming to the classic servers, despite that being the point at which most players agreed that the game lost its way.

Although, along with this announcement came the reveal of something else that players had been fantasizing about for some time.

Among the community of players who spent most of their time with the game on Classic, there was a common fantasy about something that they dubbed “Classic+.” It was to be a version of the game that, much like Oldschool RuneScape, would use these Classic servers as a jumping off point for brand new content which would be developed in line with the design sensibilities of old.

And earlier this month at Blizzcon, it was revealed that there would be new endgame raiding content, albeit made from repurposed assets, for players to engage with. However, it was also explicitly stated that Blizzard is open to the idea of resurrecting unused content, or making new experiences altogether for these servers.

For the time being it seems that Classic+ is real, and should the response be positive, I can only imagine that it will become a massively successful move for the game.

Speaking of successful live service games, Fortnite is also starting its journey through the pattern of revisiting old content. Albeit, in a uniquely expedited fashion. And in order to explain why that is, I’ll need to give you two important pieces of context.

At its core, being both a first-person-shooter and a live-service game, Fortnite is a much different case than an MMO like WoW or RuneScape. MMOs are made to be added onto, and players expect the worlds to change and their characters to play a bit differently with each successive update. While competitive shooters, on the other hand, typically rely on static and predictable behavior in gameplay, mechanics, and even visuals.

This is why something like Counter-Strike, despite having multiple versions, largely plays the same. Of course, there are differences between CS 1.6 and this year’s Counter-Strike 2, but that’s besides the point.

The point I am trying to get across however, is that when an FPS changes too much it risks alienating the players who originally made it popular or viable in competitive spaces. If the changes go far enough, this can even create “generational” divides between players who picked the game up at launch, and those who only recently got into it. A schism of sorts will inevitably form between these groups of players, both sides of which will have very different ideas about the kinds of design philosophies that the game should adhere to.

And at the rate at which live-service shooters are updated today, these generations of players are being divided up constantly, quicker and quicker than ever before. Leaving the game’s playerbase without a single common consensus on what they think the best version was. This is exactly the position that Fortnite is in today as a result of their infamously fast update cycles.

Secondly, Fortnite is also being positioned by Epic Games as a contender in the already-failed sphere of “metaverses.” With really the only successful example to chase probably being Roblox, Epic spent the better part of 2023 pushing and updating its tools for users to create their own games and worlds. With a rather sizable update in March of this year, they introduced a set of tools called Unreal Editor for Fortnite, or UEFN for short. Which obviously leverages the power, flexibility, and ease of use that comes with Unreal Engine to allow players to make those aforementioned Roblox-esque experiences.

UEFN allowed players to not only take advantage of a far more complex toolset than Fortnite’s creative modes had afforded before, but it also crucially allowed players to create and import assets from outside of the game into these new modes.

Naturally, with dozens of distinct groups in the playerbase all begging for the game to revisit their ideal version of Fortnite, the first things made with these UEFN tools were remakes of older Battle Royale maps. In fact, before the UEFN update had even dropped, there were a handful of creators who had been given access to the tools early and had begun to hype up their competing versions of the same maps.

Most of the maps being created for this UEFN arms race were remakes of the Chapter 1 island. And upon launch, these maps were very successful. However, Epic had to put a stop to them as there were pretty strict rules about importing copyrighted assets into UEFN maps. Although they did allow remakes of maps from Chapter 1 specifically to stay up.

Epic Games is seemingly aware of this inevitable yet rapidly-growing divide amongst their players, as well as their equally-inevitable desire to take matters into their own hands when it comes to accessing old content, as the developer has opted to make the current season of Fortnite a throwback event featuring the original Chapter 1 map, items, weapons, and vehicles.

And remaining in line with the past two games we’ve already discussed, this decision proved to be wildly popular.

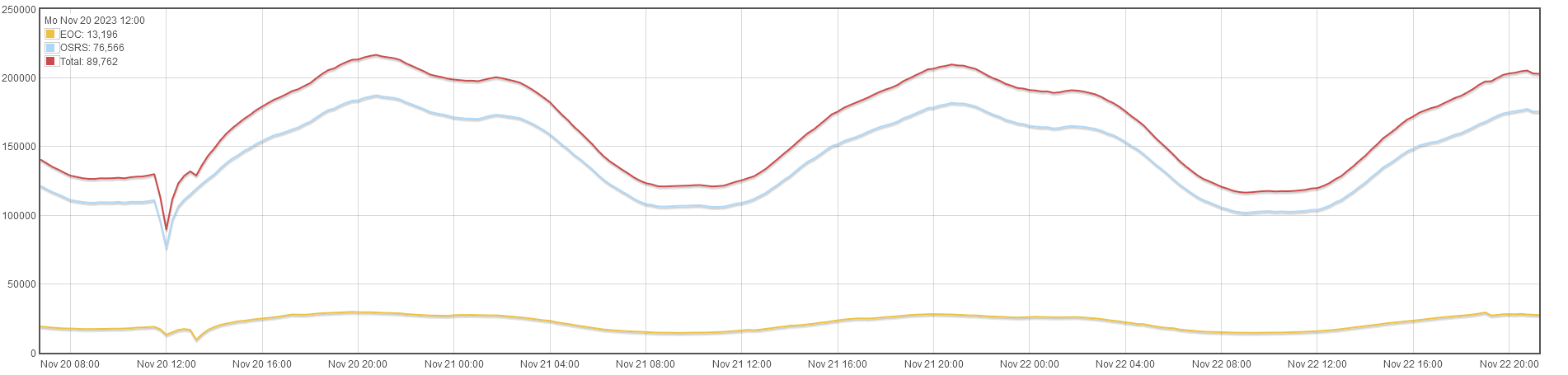

After the release of, “Fortnite OG,” the game saw its biggest day ever in terms of unique players logging onto the servers. Just to repeat for clarity, one of the most profitable video games of all time had its most successful day in its 6th year running, all because they pushed an update featuring exclusively old content.

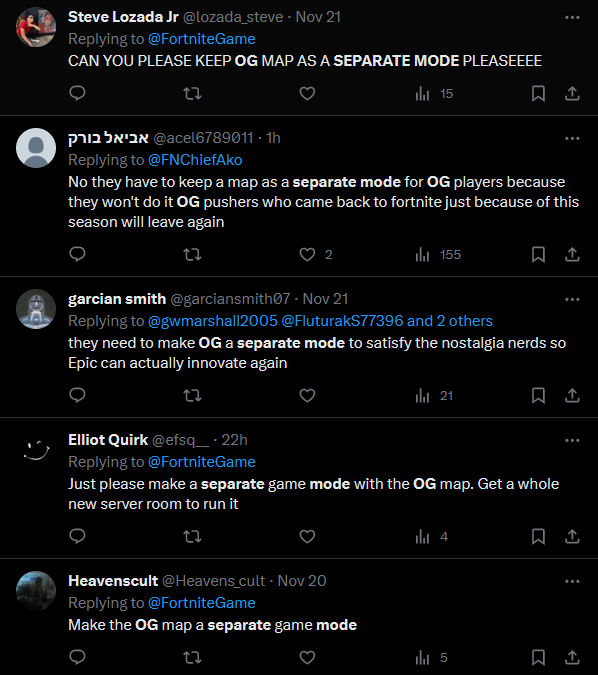

Now, Fortnite OG is actually a much shorter season than usual, lasting only a month, during which the game will rotate through different batches of older content on a weekly basis. So we won’t really get to see the entire pattern play out in terms of whether or not this old content would sustain any player retention beyond this scarce re-introduction. However, players have already begun to ask Epic Games to leave the “OG” content in the game as a separate mode. Potentially even one that could see updates of its own, should the pattern prove to repeat itself again.

Regardless, I think it’s clear that this cycle of moving on from content, eventually revisiting it in a ploy for nostalgic players to return, and then placating them with updates that cater directly to their desires is an almost surefire way to reinvigorate an aging live-service.

ANALYZING THE PATTERN

It’s also interesting to note however, that these classic, oldschool, or OG servers not only seem to last should they receive unique content, but they tend to do better than their contemporary counter-parts. What fascinates me about this emerging pattern is that it begs questions of what it is that makes the older design philosophies so appealing, why it is that developers consistently drift away from them over years of updates, and how they could potentially avoid the need to go through with these re-launches of old content or the even potential need to branch their games into separate experiences.

Is it always a matter of developers alienating their core playerbases in attempts to chase larger, yet more casual audiences? There’s an obvious pattern of the introduction of increasingly intrusive and more expensive monetization, but I don’t think that necessarily spells doom for these games. After all, most of these old content servers feature some kind of monetization today that the original versions never had. It’s also worth pointing out the very likely scenario in which these games stagnated the ambition of their updates in order to preserve core design philosophies and lost players simply due to boredom and to games whose updates might have seemed more, “dynamic,” in comparison. Like we discussed earlier, these games become solved and need far more radical shake-ups in their mechanics and design to stay interesting over the course of years-- and sometimes even decades.

For example, WoW would not have likely survived in its current form to today had they continued to pump out expansions with ambitions no greater than that of The Burning Crusade or even fan favorite, The Wrath of The Lich King. The audiences for live-services are increasingly impatient with games that cannot keep pace or scale to match growing expectations.

This could be arguably disproved by the success of something like the new content being added to Oldschool RuneScape, but in reality I think it’s less to do entirely with design philosophy itself and morseso contingent on a player’s ability to access that version of the game.

This constantly emerging pattern is symptomatic of the possibility that development on video games should be allowed to... end. In the olden times, meaning anything before the release of Destiny or Overwatch, developers and publishers used to release sequels to games. Even franchises that have moved on to live-services like Halo and Battlefield used to drop a game, update it for the next 10-11 months, and then spend the next few years taking the lessons they learned to make a bigger and better version of that game. And in the meantime, players were actually free to play other games! It also meant that players were allowed to revisit old content or stick with a version of a game they liked, rather than being forced to abandon maps, modes, and even possibly items they had worked to acquire.

Destiny is an interesting case study for this, because you can actually go back and play that game as it was when Destiny 2 released and Bungie moved on. Someday the servers will be shut down, but it’s nice that the option exists for players to go back and experience old content, or to even potentially keep playing the game they love, despite it seeing no further updates. However, of course, the same cannot be said for Destiny 2, because that game is still being updated and infamously removes content on a yearly cycle.

At its core, this pattern exists because there’s no legal or easy way for people to access content lost to the cycle of updates that live-services necessitate. Whether that be for purposes of nostalgia or because the game truly used to be better than it is now. It’s why every multiplayer map in this year’s Call of Duty: Modern Warfare III is ported over from 2009’s Modern Warfare 2, and why Halo Infinite is currently running an event (sponsored by Mountain Dew) featuring playlists made up entirely of map remakes from 2007’s Halo 3.

To bring things back to RuneScape once again, those private servers I briefly mentioned beforehand, and similar projects for World of Warcraft, were successful without any new content. It wasn’t just nostalgia in that case, certainly, because these private servers also provided largely different ways of experiencing this older content.

It’s a unique issue with odd solutions that pretty much don’t exist in any other medium. Sure, there are a few exceptions like the special editions of Star Wars largely being the only versions of those films available for public consumption, but if you can manage to track down a copy you don’t have to worry about whether or not you’ll be able to view it. Or, at the very least there are far fewer hurdles to doing so. To play an old version of a live-service game, there typically has to be servers to connect to, or an immense amount of technical skill applied to even get the game running on modern machines. That is, if the game even got a PC release in the first place and doesn’t require some kind of emulation solution like in the case of SEGA's long-dead console MMO, Phantasy Star Online.

Hell, there are even versions of games I played that I wish I could access today through this method of live-service relaunch.

One of my favorite games of all time is PUBG, but really only the version I played in 2017-2018. Not just because of the nostalgia I have for that game, but because I genuinely think it was better in its more simplistic forms. I waxed poetic about how I quit Overwatch this year, simply because I think that Overwatch 2 is an inferior game to the one that I was playing in even... 2020. In just those two cases, there is literally no way for me to experience those games as they were when I enjoyed them the most.

This even goes beyond being an issue that affects solely a game’s own playerbase. From a perspective of preservation, those versions of Overwatch and PUBG are effectively lost media. Sure, they probably exist on a server somewhere inside their developer’s offices, but that isn’t always the case and relying on a single party to do that preservation work is never a good idea. Especially when the only people who could do that work are in no way motivated from a monetary standpoint to do so.

This act as a historical exhibit is another underrated “feature” of these content re-launches. But, if it’s left untouched for too long players won’t really stick around.

I know quite a few people who weren’t playing Fortnite in 2018 who have been excited about and are enjoying getting to play with content that is effectively new to them, as well as having the ability to gain some context for the history of a game they now play. New content being added to Oldschool RuneScape allows the game to actually grow, and that’s why it’s successful in the long-term. People who have no nostalgia at all for the 2007 version of the game get to see what all the hype was about, and then also get to work towards playing through current content with new and old players alike. In both of these cases there’s an appeal to start playing, and then reasons to stay.

Despite being extremely popular, WoW Classic servers eventually see an intense player drop-off because the solved content stays solved and there’s no reason for people to stick around. Old or, more crucially, new players alike. Sure, it’s neat to see the old worlds you may not have gotten a chance to before, but it’s less fun when all of the other players are rushing you along because there’s already an effective way to solve each of the game’s problems.

Ultimately, it seems there’s no truly elegant way to handle these issues. A developer could always take the approach of something like Minecraft which allows players to install almost any previous version on a whim, but that game isn’t dependent on servers being hosted somewhere else in order to function. They could allow players to host their own servers like most multiplayer games used to back in the day, but I think we’re kidding ourselves if we think Microsoft is going to let us run Call of Duty matches outside of their microtransaction-laden ecosystems.

And for a pattern which seems so inevitable to all of these long-running live-services, you’d think that developers would try and hold their game in line with the design philosophies that players seem to hold dearest. But I think it’s impossible to see what those “correct” choices are without the context of hindsight. After all, players, more-often-than-not, have some very incorrect ideas about how to fix the games that they play.

Live-services have taken over the video game industry. Games that only half a decade ago, like Rocksteady’s upcoming Suicide Squad: Kill The Justice League, which would have been purely offline singleplayer experiences, are now being retro-fitted with battle passes, time-sink mechanics, and online multiplayer which seeks to keep players engaged for as long as possible. It is a facet of this industry which those at the top have deemed the most potentially profitable, and living in a capitalistic society, that is what drives trends in media’s most valuable sector.

And with this shift towards being always online and the death of the sequel at the hands of perpetual update cycles, this pattern of losing and regaining content is the reality of playing games going forward.

If the pattern always emerges in live-serves, and every game is a live-service, then we are due to see it many more times to come.

In evolution, there’s a concept called carcinisation. It essentially posits that all living creatures eventually evolve into something resembling a crab. And I’d just like to posit that all games today are fated to turn into live-services with multiple content branches.